Tuscany is one of the most popular destinations for wine tasting travelers. It’s where Chianti comes from. And Brunello, Vino Nobile and Vernaccia. And while they’re in Tuscany, many visitors also want to see Florence, Siena and even Pisa, just to see the tower lean. We’d like to offer another Place to Visit: Lucca.

Some may have heard of the city because it’s famous for producing some of Italy’s best olive oil. Others may know it as a well-preserved Renaissance town, still surrounded by broad walls. And it is near the area where Bolgheri, the king of the Super Tuscans, is made from Bordeaux grapes.

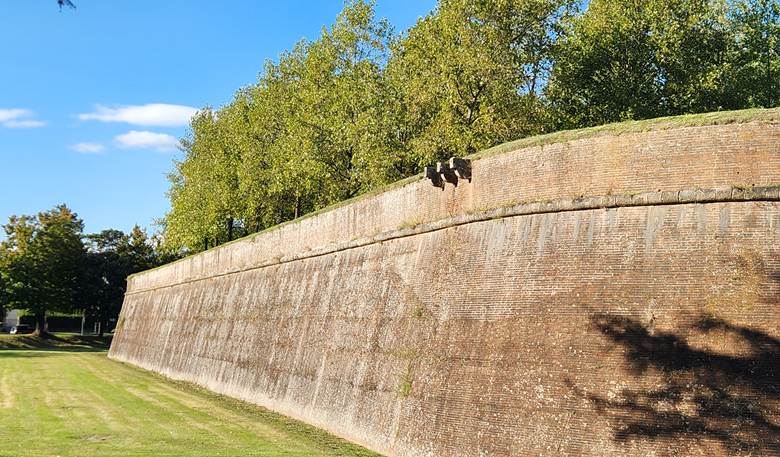

The broad walls of Lucca.

Today, Lucca has its fill of tourists, but not as much so as its more famous Tuscan cities. And it is well worth visiting for a day. The city is rich in historic sites (and sights). The walls were built to protect Lucca from its rapacious neighbors, Florence and Pisa. As gunpowder changed the nature of war, the Luccans reinforced their walled city with broad earthen ramparts. The walls worked; the city was not attacked. Of course, they don’t serve a defensive purpose today, but visitors can promenade among the treetops along the walls today.

The piazza in front of the Church of San Michele in Foro.

Inside those walls there are two very notable churches. One is San Michele in Foro, erected on the site of what had been the forum in Roman days. It is a massive structure dominating what is still a wide piazza and the principle meeting spot in Lucca today. The other is the city’s cathedral, which also has a bit of history. There has been a church on that spot since the sixth century. The cathedral there now was “only” finished in 1204.

As mentioned, Lucca attracts many tourists. There is a parking lot near the main gate into the city leading onto a long, narrow street that leads eventually to the Church of San Michele in Foro. It is a long strip of stores catering to visitors. That’s not to say that everything is tourist claptrap. The leather goods of Lucca are esteemed as are the woolens made, no doubt, from sheep raised in the hills around the city.

The Piazza dell’Anfiteatro in Lucca.

Perhaps the most popular place for visitors to Lucca is the Piazza dell’Anfiteatro, an oval-shaped space that was once the amphitheater where residents of Luca (as Lucca was in Roman times) saw plays and concerts. The theater has long been destroyed but the piazza retained its shape. Today, it is surrounded by restaurants, each with its umbrellas and outdoor tables. The owners of each one of them will tell you that they alone serve the true and ancient cuisine of Lucca.

One Luccan specialty is a pasta that they call Tordelli Lucchese. It’s a relatively thick ravioli filled with beef and/or pork, local spices and vegetables, served in a hearty meat sauce. Even on the warmest days, a bottle of local red wine is de rigeur. And to eat it where Roman actors once declaimed Plautus adds something unforgettable.