Of course, there’s a wonderful Rhone wine called Châteauneuf-du-Pape. It comes from the vineyards around a Provencal village called, well, Châteauneuf-du-Pape. In French, it means “the Pope’s new castle”. The town was there before the Popes arrived in the 14th century, due to the Babylonian Captivity that split the Catholic Church over matters of…oh, you probably don’t care. It seems that the 14th century Popes didn’t actually live there (they were in nearby Avignon) but one of those Popes built a castle and town has been named for it ever since. The castle survived for many centuries until more than half of it was destroyed by the German army at the end of World War II. The remains dominate the village to this day.

The castle ruins atop the village of Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

The village of Châteauneuf-du-Pape is located on a hill, with winding streets that lead up to and around the castle ruins. If you visit Châteauneuf-du-Pape your objective will likely be to go wine tasting; there is no denying the appeal of these fine wines. But the renowned vineyards and tasting rooms are located in the flatlands around the village, not on the hill itself. We don’t want to drag you away from wine tasting – never! – but we do recommend that you save a little time to visit the village itself.

You can and should walk up to the top of the hill to see what’s left of the castle. If you’ve seen Greek or Roman ruins, you know that there is a melancholy poetry to what is left of destroyed ancient buildings, and so it is in Châteauneuf-du-Pape. Moreover, you have the views from there of some of France’s greatest vineyards, stretching out to the horizon.

There are other attractions, such as an old church, a pretty fountain, tasting rooms, wine stores and even a wine museum. Still, Châteauneuf-du-Pape is just a small French village, with less than 3,000 residents. But it is a village with money, derived from the wine trade. So it is a spic and span village, ready to welcome visitors. It looks very much like the French village you dreamed of, which so few actually are.

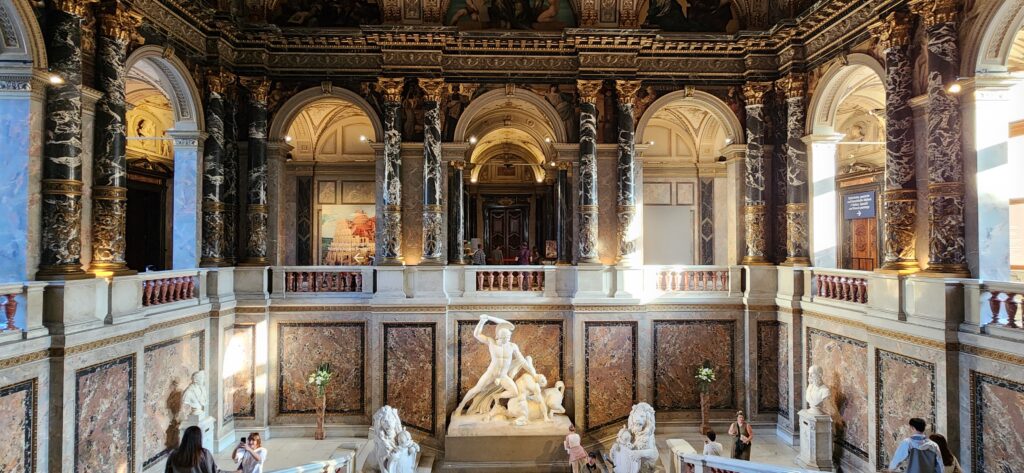

Photo courtesy of Booking.com.

If you come to Châteauneuf-du-Pape for wine tasting, complete the experience with a stellar meal. There is no shortage there of restaurants, cafes, bistros and watering holes. After a few hours of tasting wine, or maybe the next day, you’ll be ready to settle down with some Provencal cooking and a bottle of, well, Châteauneuf-du-Pape.

In good weather, you can dine outdoors with those vineyard views and, on a clear day, of the Rhône river just beyond. Buttery croissants in the morning; pâté and cheese for lunch; local leg of lamb roasted or venison stew for dinner. Yum! Of course, this being in the heart of French Wine Country, there is haute cuisine to be had as well. Châteauneuf-du-Pape is a small village, but it boasts eleven restaurants listed on Michelin’s website. Almost by definition, all these restaurants have fine cellars to match their cooking. What more could you ask for a southern French experience?