We like wine; we know a bit about it; and of course we publish Power Tasting. We’ve had some friends and acquaintances who are aware of our oenological tendencies tell us that they/their neighbor/their father-in-law makes wine at home. And they always tell us it’s as good as the best from Napa/France/Italy. There’s no way to put them off by saying, “I’m sure it’s quite good”. They insist on giving us a bottle to hear our opinion.

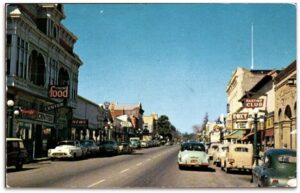

Photo courtesy of the San Diego Amateur Winemaking Society.

We suspect they never tasted Petrus and certainly not their home-made wine next to a glass of it. So we sip what they give us, hoping that it isn’t vinegar, swirl it in our mouths a while and then, trying hard to look earnest, tell them that while theirs is interesting, we prefer to stick with the wines we know. Notice the absence of any actual opinion.

This experience comes to mind in our wine tasting travels because quite a few wineries offer the experience of making your own wine. We are aware of several that have similar programs, including Conn Creek and the Wine Foundry in Napa and several places in Texas called Water2Wine. We have tried our hands at blending at Joseph Phelps in Napa Valley, trying to replicate Insignia, their flagship wine. We have concluded that a) we are not very capable winemakers and b) professional winemakers do an awfully good job.

Neither of those points should have come as surprises. We have no training, no experience and, though we hate to admit it, probably no aptitude for winemaking. We don’t expect rank amateurs to do our jobs, so why should we be expected to become skilled professionals just because a fine winery has given us some fermented juice to play with.

We have been fortunate enough to spend some time with several real winemakers from wineries we admire and we have great respect for them. It’s not just that they have skill at blending varietals. For one thing, they have well-cultivated tastes for wine. Sure, we do too, but we only taste the finished products. They can sip a little of this, a bit more of that and figure out what combination will be consistent with the production of years past and will taste good years in the future.

We’re happy to leave our expertise at opening bottles, pouring wine into glasses and having enough insight into wine to distinguish well-made ones from plonk. At best, we know the difference between good wine and really good wine. Which brings us back to the wines made at home. There are home cooks who can make a great, restaurant-quality meal but not hundreds of meals of exactly the same quality every night for years. The same applies to amateur winemakers. We’re certain that they enjoy what they’ve made, if only because they get to drink the results of their own handiwork. We’ll go further and recognize that if they like their own wine, that’s their own business. But they cannot make great wine, just wine they like.

Having had the chance to make our own wine, we’ve decided to let the professionals do their thing and we’ll do ours: drink it and enjoy it.