Napa Valley is the most beautiful winemaking area in California. It stretches 30 miles between two mountain ranges, the Mayacamas and the Vaca. There are hundreds of wineries there and many of them are the most famous in America. We always have a wonderful time when we visit there.

Sonoma County contains the most beautiful winemaking areas in California. There are several distinct growing areas, several of which specialize in certain grapes. There are hundreds of wineries there and many of them are the most famous in America. We always have a wonderful time when we visit there.

Does that sound just a tad schizophrenic? Well, there’s a lot of truth in that. Both Napa Valley and Sonoma County are very special places for us and we visit one or the other or both almost every year. That raises a question that is the theme of this article: for the wine tasting visitor, as opposed to a winemaker, are they two distinct places or just one, divided by mountains?

The view from William Hill in Napa Valley

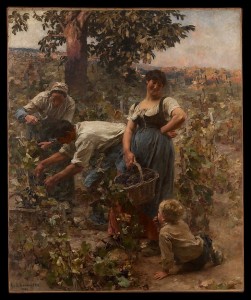

The case for distinctiveness starts with the grapes. Chardonnay is grown plentifully on both sides but Cabernet Sauvignon (and to a lesser extent, Merlot) is the king of Napa Valley. Sure, there is lots of Pinot Noir in Carneros on the south end, but that sector is split between Napa and Sonoma Counties, so by definition Carneros is an outlier. Sonoma County also has lots of Cabernet Sauvignon, but it’s concentrated in Alexander Valley and Chalk Hill. Zinfandel is in Dry Creek and Pinot Noir is the star in Russian River, Green Valley and the aforementioned Carneros areas.

[To be sure, all the foregoing is an over-simplification. You can find some of everything everywhere. But the reason that the wines in each AVA are world-famous is because of the grapes mentioned.]

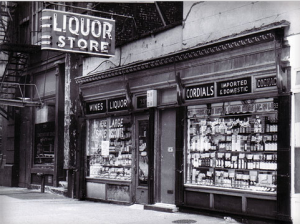

The view from A. Rafanelli in Dry Creek

Of course, they’re much the same as well. Both Napa Valley and Sonoma County have great restaurants, attractive wineries and ample opportunities to learn about wine. Sadly, the hotels on both sides are getting waaaay too expensive, as are the charges for tasting. They both offer mountain and valley fruit, along with the disputes about which is better.

The strongest argument for treating Napa Valley and Sonoma County as one wine tasting destination is the ease of traveling between the two. Route 121 traverses them both on the south end; the glorious Oakville Grade is in the middle; and Mark West Springs/Petrified Forest Roads are at the north. Or you can continue up Route 29 until it leads you into Alexander Valley. The counterargument, by the way, is that you shouldn’t attempt the mountain crossings at night after a day of wine tasting. We learned that lesson the hard but fortunately safe way.

For many years, we visited one or the other but not both. Recently, we have been packing our bags and spending a few days in Napa Valley and then a few in Sonoma County. That’s great if you have the time. But this strategy doesn’t answer the question as to whether they are one place or two. At the end, we say that the answer is “Yes”. They are one place just as Manhattan and Brooklyn are both New York and they are different for just the same reasons. They are much alike but they feel different. A Sonoman tell you that they are jus’ folks and the Napans are snobs. Napans say that they are cultured and the folks on the other side are hicks. There are palaces in both places (although more in Napa Valley). There are interesting little out-of-the-way places in both but more of them in Sonoma County. Visit both. Reach your own conclusions. Enjoy the wine.